Manning's Project Uncovers Lost Stories of Mill Children

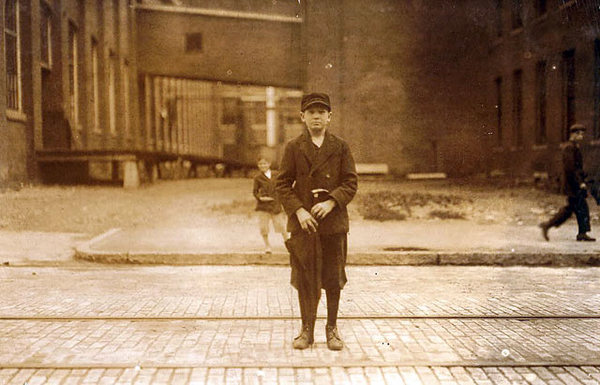

Local writer and historian Joe Manning has spent three years researching the children in Lewis Hine's child-labor photos. Top: Hine's captions haven't always helped. The 13-year-old boy he identified at the Hoosac Mill in 1911 as Joseph Crapo of Fruit Street was really Joseph Crepeau of Front Street. |

"I spent an intense two or three months digging into Addie's past," the Florence resident said in a recent interview. "Standing at the gravesite was very eerie."

The 12-year-old Pownal, Vt., girl pictured in a Lewis Hine photograph had inspired a book by Williamstown writer Elizebeth Winthrop, who had charged fellow writer Manning with discovering the truth about her.

With a love for history and geneaology, Manning was the perfect detective. He scoured town records and poked through cemeteries, eventually finding the little mill girl had lived to the ripe age of 94.

And then it was over. "I was down in the dumps," he said. "There wasn't anything else to do. I did it but the shine was gone."

Until he began browsing back through the 5,000 other photographs archived in the Library of Congress that Hine took on his trip around the country documenting the evils of child labor after the turn of the last century.

Two little girls caught his eye. He wondered if he cound find them as he had found Addie. Did they grow up to have families? Had they moved? Had they escaped the poverty that had forced them to work long hours in a North Carolina cotton mill?

Only one girl was named, Minnie Carpenter; the photo was taken in Gastonia, N.C., in 1908. That was enough of a lead — Manning started digging, using online databases and calling the Gastonia library.

He found Minnie's obituary from 1973. She'd never married and only had a few survivors, including a nephew. A man by that name was still listed in the telephone directory for Gastonia. Manning called him and, yes, he was the nephew. So Manning mailed him a copy of the picture to see if he could identify the other girl.

"I waited two weeks and called him back," said Manning. "He said, 'the other girl is my mother. I've never seen a picture of my mother as a little girl.'"

Lewis Hine

Minnie Carpenter, left, and her sister Mattie Carpenter of Gastonia, N.C. |

Manning told his wife what he had done. "Well, she said, I guess I'll never see you again," he said. "That was three years ago."

Since then, the frequent city visitor has investigated 130 photographs with varying degrees of success. And he doesn't plan to stop; the children in these pictures are quietly calling him to discover their lives, their reality. To document those things that made them real people.

"This is an iconic photograph that's admired these days not for its child labor subject so much as it is for its artistic content," said Manning. "But it's a real person. [Answering those questions] turns that photograph into a human being."

Even more compelling is the uniting of families with a picture of their relative they often didn't even realized existed. Three families have even invited Manning to their family reunions.

"It's had an enormous impact," he said. "It's hard to underestimate the power one has to enrich somebody's life by giving them this picture they never knew about."

It's not all happy endings. Two boys grew to manhood in the coal mines, only to die in accidents as adults, each leaving behind a wife still pregnant with their first child. But others, such as Joseph Crepeau of North Adams (pictured top), lived into their 90s.

His work, documented to large extent on his Web site, has drawn interest from media, publishers, academics and Hine aficionados. His Web site has been averaging 100,000 hits a month and its in the top five for searches for "Lewis Hine."

Manning is in negotiations with a publisher to present his work in book form. A University of Michigan professor has selected his ongoing research and that of archival photographer Rich Remsberg of North Adams for a study on how researchers use the Library of Congress to evaluate possible improvements in the system.

But Manning isn't a Hine expert. He's more interested in the children that Hine used to show the plight of the child worker.

Groups have researched Hine photos before, but usually for local subjects. To his knowledge, he's the only one searching through the entire the collection, taken over a decade in 32 states and the District of Columbia. He's been trying to be equitable in chosing gender, ethnicity, location and industry.

Ten years ago, his project would have been nearly impossible and incredibly expensive. But with the proliferation of free and paid databases, as much as 85 percent of his research can be done from his own office. The rest by phone, mail and the occasional local trek.

A name is preferable, especially an unusual one, to start a search, although Hine wasn't nearly as good a speller as he was a photographer. Ages attached to the photos are also often incorrect, too, said Manning.

Eleven of the photos he's research had no name attached, just the location. In one case, Manning turned to the local newspaper to identify the picture of a girl taken 99 years before. Within 24 hours, he had an e-mail from the girl's daughter, who was shocked to open her daily paper and see her mother on the front page.

His research is a labor of love; the reward is closing a chapter on a once-unknown life.

"It satisfies my historical curiousity and I'm doing a service to history," said Manning, comparing it to his earlier books of interviews with North Adams residents about the city's industrial age. "I get a tremendous amount of enjoyment doing something I love doing.

"I like to tell stories ... I like to tell real stories."

Manning will discuss how he does his research, displa the photographs he's identified, including a number taken in North Adams, and share the stories he's uncovered on Thursday night at 7 at MCLA Gallery 51, 51 Main St.