Sagas of the Shire: The Madness of Sue Dunham

Susan Dunham was a local legend in the hills and dales of the Berkshires. Susan Dunham was a local legend in the hills and dales of the Berkshires. |

SAVOY, Mass. — Author Thomas Pynchon called her "that beautiful and legendary drifter who last century had roamed all this hilltop country, exchanging babies and setting fires."

From depictions in literature and in visual art as well, there can be no doubt that the strange sad life of "Crazy Sue" left a significant impression, even on the memory of a region somewhat known for its eccentric characters.

"For fifty years, through the storms and heat, ice and snow, Sue traveled the roads of Berkshire, a poor, wild, aimless, and harmless being who recognized no family and no home," recalled the Berkshire Hills WPA Guide in 1939.

Susan Dunham was born on Martha's Vineyard in 1777, to parents Cornelius and Tabitha Dunham, who later resettled to the Berkshires. Little is known of her early life, before she came to be known as "Crazy Sue," other than that she is thought to have been considered very attractive in her youth, at least once referred to as the "belle of Savoy."

She was born in an era where ailments of the psyche were barely comprehensible, yet nonetheless intriguing — and generally only tolerable to think about through a lens of humor or literary romanticism. So what it was that first drove Sue "crazy" is a matter of great folkloric speculation, and accounts offer various scenarios. Not surprisingly, the most prevalent legend is that her "madness" was the result of a tragic love story. It was rare to find any storied hermit or "local lunatic" of the 19th century, in the Berkshires or anywhere else, whose behavior was not ascribed to some past romantic misfortune.

An alternate explanation is that Dunham never recovered from the influence of hysteria brought on during one of the town's flamboyant religious revivals. Savoy was a particular hotbed of impassioned revivals by several sects in the early 1800s, and more than one town historian has indicated the frenetic quality of some of these revivals had lasting psychological effects on its residents. Records show a number of suicides among converts in the aftermath, and at least one was left in a state of such "agitation" that he was placed in chains for the remainder of his life.

An oft-repeated legend of Sue combines the two rationales. In it, Sue falls in love with a young man of ardent Jeffersonian political leanings, but the match is forbidden by her father, a fervent Federalist. It is a theme not without precedent in the deeply divided political landscape of the time, a rift known to have torn asunder families, churches, and threatened the stability of whole towns.

It is following the dissolution of this forbidden romance, the story goes, that Sue "came under the spell" of a mesmerizing itinerant preacher, and was never the same again.

Despite its almost too convenient thematic reasoning and historical context, this bit of back story may not be entirely without some basis, for Sue herself once remarked when asked the cause of her malaise: "A little politics, and a little religion."

Anecdotes that survive of Susan Dunham suggest that the nature and cause of her mental state was of less interest than the reactions to her unorthodox ways, which range from mild amusement to a deep respect for her intelligence and wit.

"Since insanity was widely regarded as an occasion for tasteful humor, many Berkshire residents thought to make sport of poor, mad Sue," according to historian Bernard Carman. "But those who attempted to demonstrate their own superiority were frequently brought up short."

One such instance often retold involves an encounter with Sue by William H. Tyler, an eminent doctor, and attorney George Nixon Briggs, later a seven-term governor of the commonwealth. Coming upon Dunham fishing in a stream, the duo asked her, rather obtusely, what she was doing.

"Fishing," Sue called back.

"What do you hope to catch?" they chuckled.

"The Devil," she replied, without looking up.

"And what are you using for bait?"

"Doctors and lawyers."

It was perhaps her shrewd tongue that most contributed to her status as a legendary local figure during her lifetime, fueling a general affection that excused frequent misdemeanor infractions.

Among these was a penchant for playing with fire, such as in one well remembered instance while boarding at the Savoy home of Abel West. Awakened by the smell of smoke, West ran downstairs to find a blaze roaring up his mantle, from the pile of her clothing she had tossed into the fireplace. Sue sat calmly before the fire, wearing virtually the man's entire wardrobe.

"I heard Cain killed Abel," cackled Sue, "So I thought I might as well have Abel's clothes."

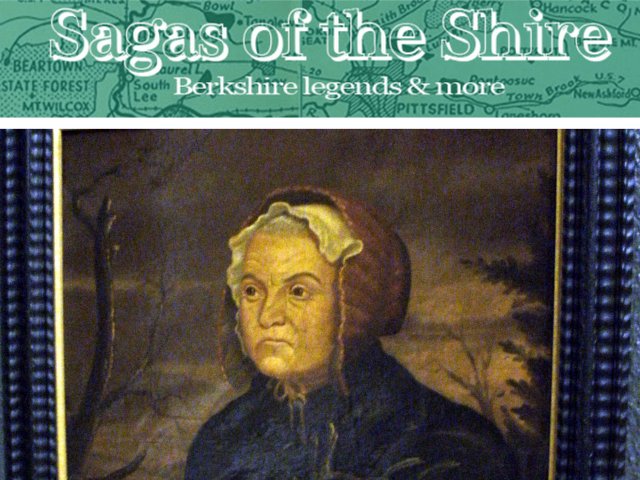

Dunham's portrait, by George Williams, hangs in the Berkshire Museum. Dunham's portrait, by George Williams, hangs in the Berkshire Museum. |

One of her favorite pastimes was duping the unsuspecting with a pious call to prayer. Once she had convinced them to bow their heads and close their eyes with her invocations, she quickly helped herself to food, silver, and any other small items that struck her fancy.

On at least two known occasions, Sue helped herself to a new mother's baby, swapping it with that of another. Even this was taken more or less in stride by generally tolerant locals, and Dunham was rarely hassled by law enforcement.

Toward the end of her days, one incident of taunting by some young men appears to have gone too far. Among Sue's habits was a tendency to mourn, sometimes for days on end, at the graves of young men, even if she had not known them. On one such occasion a group of students donned burial shrouds and began popping up around her, attempting to scare her. She took no notice.

Finally, one of them called out in a deathly voice, "Susan Dunham, where art thou?"

"Here, Dear Lord!" she called back miserably.

The next day she departed to the home of her brother in Windsor, living out the rest of her years quietly in solitude. It is said that at the end of her life, a clarity of mind returned to her, in which many of the preceding years of her life were lost as though to amnesia. When shown her reflection in a mirror, she did not recognized her aged face.

She died a few days later, on Dec. 14, 1852. An overflowing crowd attended her funeral at Pittsfield's South Congregational Church, after which she was buried in Windsor.

The stories of Sue survived long after her passing. She forms the substantial basis of the character of "Crazy Bess" in the New England Tales penned by Catharine Segwick, at whose home Sue was a frequent caller, and she is referenced in Thomas Pynchon's short story "The Secret Integration" as well as his novel "Gravity's Rainbow."

Images of her can be seen to this day in the Berkshire Museum, whose collection includes a portrait of her by painter George Williams, and also in a piece of Blue Staffordshire pottery by James Clews, of Park Square and its legendary Old Elm.

Sue Dunham, herself now as much a feature of legend as the ancient tree, can be seen in the foreground, where she is was seen often, picking up litter from the park.

The writer of this column, Joe Durwin, has recently launched a campaign on Indiegogo.com to fund the publication of a new collection of writings on local folklore and history.

"These Mysterious Hills: An Unauthorized History of the Berkshires" represents the culmination of more than a decade of writing on all things weird in the Berkshires and surrounding area, and covers a wide array of curiosities from three and a half centuries of recorded history in the region. By shining a spotlight on the area's more unusual episodes and legends, Durwin believes it will enrich knowledge of local history while attracting new tourist interest in the region.

Check out a video on the project and rewards available to supporters of the book here.