Our Neighbors: Aunt Anna's Boys

An old Sprague motor. The company's founders had their roots in North Adams and the aunt who raised them is buried in Hillside Cemetery. An old Sprague motor. The company's founders had their roots in North Adams and the aunt who raised them is buried in Hillside Cemetery. |

NORTH ADAMS, Mass. — This story is mostly about someone who is buried in neither Hillside Cemetery nor North Adams. He was quite famous in his day and is still highly regarded in certain circles. His connection to Hill Side is through someone who is buried there.

Who was he? Does the name "Sprague" ring a bell?

David Sprague was born in Vermont; the family moved to North Adams when he was young. When he grew to adulthood, he left town to seek his fortune, settling in Milford, Conn., where he married and had two sons. Then his wife died. The two boys — Frank and Charles — were sent back to North Adams to be raised by their aunt, Anna Parker.

Not much is known about Mrs. Parker, except that she was a Sprague by birth. While married to Mr. Parker, she lived in Pittsfield, but after his death she returned to North Adams, presumably to be closer to her family.

When her two nephews came to live with her she was residing in a house on the south corner of Eagle and Wesleyan streets (it's still there, by the way). They attended local schools and worshiped in the Methodist Church. When they entered adolescence, they both studied at Drury Academy. Frank excelled in mathematics, but did not graduate. Being singularly ambitious, he applied for an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis.

The way this works is you apply to your congressman, who submits your name. Then you take the written tests, which are rigorous. Pass the tests and you become a midshipman at Annapolis. Fail the tests and you transfer to a prep school, where you hit the books and hit them hard. Then you apply again.

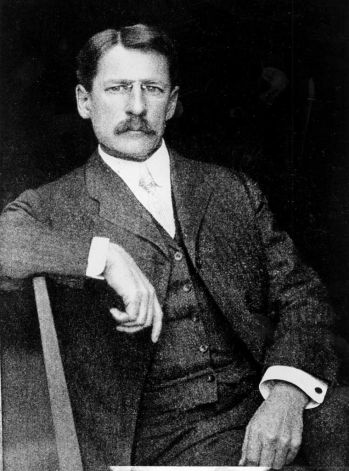

Inventor and engineer Frank Sprague in a photo taken around 1890. Inventor and engineer Frank Sprague in a photo taken around 1890. |

Frank Sprague succeeded at Annapolis, and handily; he graduated seventh in his class (of 36). He had a strong and abiding interest in electricity and once assigned to a ship Ensign Sprague treated it as his own personal laboratory. After a few years, he resigned his commission to work in the private sector, initially working for Thomas Edison.

But not for long. Edison had become immensely wealthy by way of his first few inventions. After that, he surrounded himself with brilliant young minds, told them what to work on and patented the results under his own name. Young Mr. Sprague recognized early on that if he was going to make a name for himself, he would have to do it on his own.

Independent of Edison, he invented the first practical industrial electric motor that he began manufacturing in New York City at the Sprague Electric Works. Interestingly enough, when his son's company — Sprague Specialties — moved into the Arnold Print Works' Marshall Street complex in 1940, two electric motors were found in the plant made by the Sprague Electric Works of New York.

But Frank was not willing to rest on his laurels. Having an electric motor, he began looking for diverse applications for it. His first grand scheme (that was successful, anyway) was an electric trolley system, tested and proven in Richmond, Va. The plan was simplicity itself: Run overhead wires along the route to supply power and put a motor in every car. Then, if one car breaks down, the rest of the system continues to run. Compare this to the famous cable-car system used in San Francisco. If the motor that runs the system breaks down — or the cable breaks — the whole system shuts down.

The real significance of the Sprague trolley is that it was the model for the modern subway system. Instead of using overhead wires, the modern system uses a third rail, but otherwise is essentially the same. The success of his electric trolley system brought a good deal of business to the Sprague Electric Works. But it also brought a rather large shark, in the person of John Pierpont Morgan.

As a financier, Morgan pioneered the "megacorporation." In Pittsburgh, he bought up various steel companies, mines, smelters and shipping companies to form the gigantic U.S. Steel. In New York, in 1890, he bought up a number of electric companies to form the still colossal General Electric. One of the companies he bought was Sprague Electric Works, which again, brings us to an interesting irony: When in the 1920s R.C. Sprague started his own company, Sprague Specialties, GE owned the rights to the name Sprague. He had to get permission from GE to put his own name on his company and products.

Anna Sprague Parker is buried in the Sprague plot at Hillside. Anna Sprague Parker is buried in the Sprague plot at Hillside. |

The way the sale came about — very much against Frank Sprague's wishes — dates back to when he left Edison's employ. Being ambitious and ready to work hard to achieve his goals, he was nevertheless cash poor. To establish his own company, he went into business with someone who had money. Thus his partner owned the controlling interest while Frank became the "brains."

Ultimately this meant he had a hard lesson to learn about business. It's not enough to be a brilliant engineer; you have to be in control of the business, too. His partner sold the company out from under him. Forty years later, R.C. Sprague would learn the same lesson the hard wa. Through carelessness and a bad investment, control of his company was taken away from him.

Frank was down, but not beaten. He started a new company, bringing about an innovation in elevators, by applying the same concept he used in his trolley system. By putting a motor on each car he could have elevators that worked independently from each other. This was instrumental in developing elevator systems for skyscrapers. He sold this company to the elevator giant, Otis and went on to start another. Ultimately, he became known as the Father of Electric Traction.

Frank was twice married, first to Mary A. Keatinge. They produced a son, Frank D'Esmonde, who became known by his middle name. This marriage apparently ended in divorce. In the 1890s, Frank Sr. married again, this time to Harriet Chapman, with whom he had three children: Robert Chapman (R.C.), Althea and Julian King. Like his father before him, Robert went on to study at Annapolis, where he graduated 11th in his class. Also like his father, he resigned his commission after a few years to work in the private sector. When Frank died in 1934, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Now back to his brother. Charles Sprague did finish high school. In fact, he was valedictorian of his class at Drury Academy. He achieved this by comprising the entire top quarter of his class. Yes, it graduated four people that year. He married a local girl, a Vadnais, and began raising a family. By 1900, he was living in New York City, where he worked for GE, though he later went to work for his brother.

With her two nephews grown and flown from the nest, Mrs. Parker remained in North Adams. They visited her from time to time, as happens with close relatives. When she died in the fullness of time, Mrs. Parker was buried with her parents and siblings under a white marble shaft in the Sprague lot on the south side of West Main Street. She is not averse to being called upon should you feel so moved.

This series is an attempt to help us get to know a particular community of neighbors, without whose vision and efforts this city would not exist. These neighbors are the residents of Hillside Cemetery. As part of our effort to restore and maintain this, the city’s oldest municipal cemetery, we hope to generate interest, funding and volunteer labor in an effort to restore it. This work is an important step in maintaining our city's heritage and civic pride. But more than this, it's a way in which we can help our neighbors; neighbors who laid the foundations of North Adams and paved the way for us.

Tags: hillside cemetery, historical figure, our neighbors,