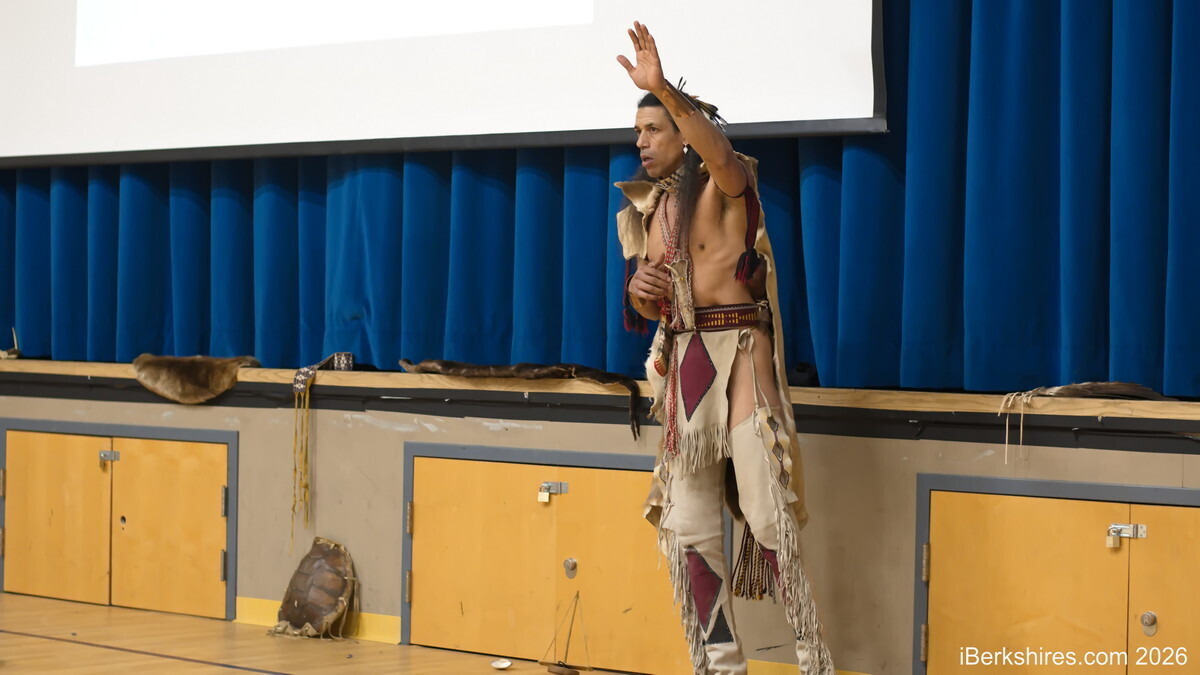

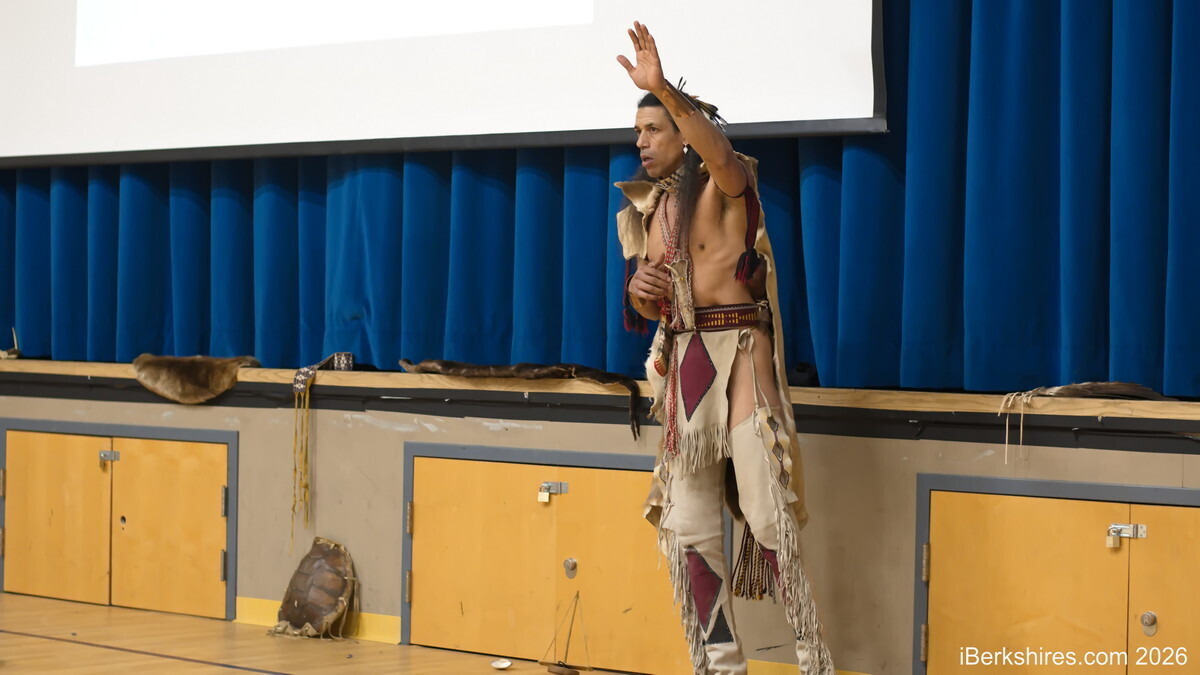

Annawon Weeden, above, notices the 'settlers' when he stops to drink water. Later, he become a whaler, telling the native story of a familiar great white whale.

ADAMS, Mass. — Native American actor and activist Annawon Weeden brought his one-man show to Berkshire Arts and Technology (BArT) Public Charter School, confronting students with a challenging and visceral journey through American history.

"This performance is called 'First Light Flashback,' where I hand-carry individuals like yourselves and walk you through the history, the emotions, and the struggles," Weeden said after the performance on Feb. 11. "These are some of the lowest points in humanity … it is an emotional rollercoaster."

Weeden, of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, is a consultant, presenter, and performing artist. He is the director of the First Light Foundation, which offers educational and historic programming aimed at amplifying indigenous voices and stories.

Once students were settled, the lights were cut, leaving only a spotlight on a collection of traditional objects. After an uncomfortably long wait, Weeden burst through the back doors of the gymnasium, acknowledging the "settlers" in the auditorium only after several slow, deliberate sips of water.

The timeline on screen shifted from the 15th century — a time of Wampanoag sovereignty — to the 17th century.

"You have traveled very far, yes? You are friend, yes?" Weeden asked, performing as Tisquantum (Squanto) after an aggressive standoff with the students.

Tisquantum was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Wampanoags and a liaison between the Native American population and the Mayflower Pilgrims.

"Many strangers, not friends, take Tisquantum," he said. "Two journeys across the great pond, and learned much about the Wannuxoc. Very big village. Many Wannuxoc."

In the Wôpanâak language, Wannuxoc is a term used to describe Englishmen or white settlers.

Weeden came to BArT through a Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Genocide Education Grant. The 9th and 10th graders had recently studied King Philip's War and watched the documentary series "We Shall Remain," in which Weeden acted.

During the performance, Weeden called upon students and administrators to join him in a traditional dance. He offered food and drink, asking if they were there to trade. He bypassed modern items like basketball shoes or purses, eventually settling on a gold chain in exchange for a pelt — a symbolic nod to the early trade relations that preceded the conflict.

The tone shifted sharply as Weeden began to cough, addressing the "sickness" and contradictions brought by the Wannuxoc and their bible. As the cough worsened, he admitted, "Tisquantum won't be here much longer."

The timeline jumped to the late 17th century as Weeden transformed into Metacom, also known as King Philip. He spoke of his father, Ousamequin, who had helped the initial settlers when they were ill-prepared for the land.

"Upon landing on our shores, the land you call Cape Cod, helping yourself to everything you find, raiding our families' homes, helping yourself to their food sources, their supplies," he said. "That was not enough for you. You helped yourself to their graves, unearthing the very corpses buried within. And within those graves, the most sacred objects — once again, you helped yourself."

Metacom was the leader of a significant resistance movement against the English. He was eventually killed in 1676; his body was drawn and quartered, and his head was placed on a pike in Plymouth for decades.

"The Nauset people do not want you here, and you are no longer welcome in their territory," Weeden declared.

He then referenced the Mystic Massacre of the Pequot War, in which English forces set fire to a fort, killing hundreds of men, women, and children.

"Burning innocent women and children alive while they slept. Rounding them up like your cattle, forcing them into slavery," he said. "... You celebrate how you can smell their burning, rotting flesh from over a mile away. This was your first religious day of Thanksgiving."

He cautioned the audience about the stories they pass down and the damage done to the land. As the timeline moved to the 18th century, the transformation became physical. Weeden began removing his traditional jewelry and regalia, lamenting how his people were forbidden from speaking their language or practicing their rituals.

"We were once a proud people. A proud people with much to share," he said. "Now it is we who go without. We have become strangers."

"I would be grateful if I could simply work for you on our own land," he said slowly, dressing into slacks and a jacket. "I am happy to tend to your crops ... I am grateful for my master and these fine English clothes."

Weeden then became a whaler. He told the story of Maushop, the benevolent giant who shaped the Wampanoag home, creating Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. He explained how the Great Spirit transformed Maushop into a great white whale so he could always watch over the cliffs of Aquinnah.

"He turned him into a humongous, abnormal white whale. One I am pretty sure some of you are familiar with," he said. "Does the name Herman Melville ring a bell? We are still working on the copyright infringement."

Now dressed in his "Party like it's 1491" shirt — referencing the era before colonization — Weeden opened the floor to questions. He noted that he has spent 30 years developing "First Light Flashback," following in the footsteps of his father, a fellow teacher.

"This is a powerful tool, and I was fortunate to find it," he said afterward. "It is sad that in the past we were unable to tell this story ... to get it out to more people and have more awareness."

Weeden acknowledged the visceral nature of the show, noting that it often hits harder than a textbook.

"You turn the page, you close the book, you are done. You change the channel... you are done," Weeden said. "You never get emotionally attached … until you can see it and see it embodied."

Looking back on his own education, Weeden recalled teachers who denied his history or held him to Hollywood stereotypes. He credited those who stood up for him and expressed gratitude to the educators now bringing his story into schools.

"It is my duty. It is the least I can do," he said. "They fought their wars in their ways, and now education is the battlefield."