Review: 'Moonchildren' at the Berkshire Theatre Festival

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass. — It seems impossible that eight college students living together could be desperately lonely and unfulfilled. Yet in 1965-66 when the play "Moonchildren" is set, Michael Weller chooses such a group of nerdy and naive students to populate the rundown communal student apartment in his first successful play.It's a familiar if unconventional group. They discuss esoteric ideas, eat each other's food, make love, and protest war together. "Moonchildren" is the first play written that put the spotlight on a major change in America as it comes to grips with the conflict in Vietnam.

It is also the first play that Great Barrington artist and actress Karen Allen has directed for the Berkshire Theatre Festival, though it's her second time directing "Moonchildren," having previously put a young cast at Bard College through its paces.

It is also the first play that Great Barrington artist and actress Karen Allen has directed for the Berkshire Theatre Festival, though it's her second time directing "Moonchildren," having previously put a young cast at Bard College through its paces.The time of the play is interesting, taking place just as the first peace rallies (opposing the Vietnam War) were beginning to happen. Draft cards (and bras) are yet to be burned, the first huge rally on the Boston Common is several years away, and the music has not yet been shaken and stirred with acid. Professor Timothy Leary had been dismissed from Harvard in 1963 and it would be a few more years before LSD would become the drug of choice for many flower children.

While the generation that would change social mores had not yet taken wing, we are given an intimate look at the chrysalis from which the counter-culture would emerge to became a nation-changing phenomenon. It is a time when students are evolving from prankish kids dealing with neurotic parents into what would become the love and peace generation.

The '60s followed the delinquent anti-hero '50s (think James Dean and "Rebel Without a Cause") with new role models arriving on the scene, like Bob Dylan, Fidel Castro and Spider-Man. The old ways were crumbling. Existential angst was peaking. (Edward Albee's George and Martha and Nick and Honey arrived in 1962). The old establishment was rejected, the new one yet to be created. Some of these students grew up to become the selfish single-issue politicians and the personal-profit obsessed corporate leaders that have wreaked the current financial havoc in this country.

Being rudderless can produce the benefits of endless discovery, or the tragedy of ethical and moral bankruptcy. We see hints of the latter in the relationships between the characters of this play. At the end of the play – and years of living together – there is barely a hug, or much depth to their parting. Some vacate the apartment without even saying goodbye. So much for commitment. They may be educated but they remain emotional cripples, the whole lot of them.

|

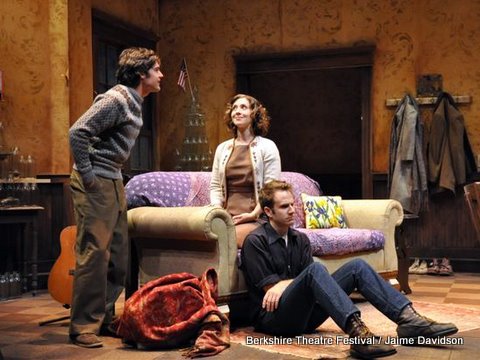

Even so, as directed by Allen, and staged at the Berkshire Theatre Festival's Unicorn Theatre, it is an interesting evening of entertainment that can bring back a flood of memories, and dredge up a dozen old philosophical arguments. This production was more fully realized than the one I saw back in the '70s.

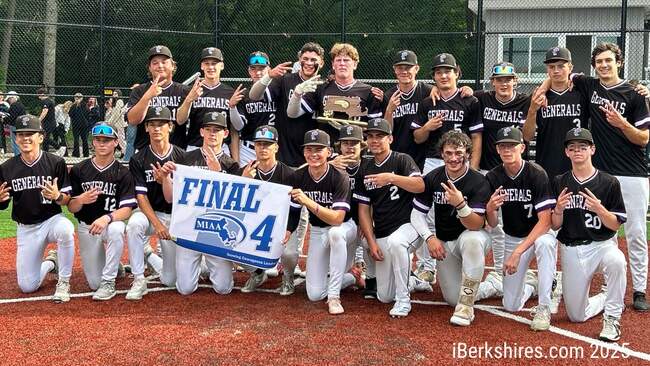

One of the wonders of this production is its cast. Allen has assembled a diverse group with widely different experience and backgrounds (BTF held local auditions for this production) about two-thirds equity actors and one-third not.

Under Allen's guidance, they have worked themselves into a group that loves practical jokes, put-ons and send-ups, replete with comic posturing by both the adults and the students. The cast is beyond college age, though some are very close, being recent graduates themselves.

Cootie (Matt R. Harrington) and Mike (Joe Paulik) are brilliant as two alike jokesters who claim to be brothers and improvise this and other elaborate lies and cruel jokes easily. They were a metaphor for a college generation who used a thin layer of dark and evasive humor to avoid making essential life decisions or entering into relationship commitments.

Director Allen keeps a steady hand on the wheel of this ensemble vehicle, never letting one or another of the actors dominate the proceedings until the end. At that point we are treated to one of the highlights of the evening – the strong and powerful work of Norma Kuhling as Kathy, whose simple silence and reactions outshine even Hale Appleman's play-ending confession (as Bob). It is both the play's most dramatic and deeply revealing moment. In the end it is her character who has the most common sense and a realistic grasp of the future.

In fact, "Moonchildren" has a number of highly dramatic and often funny moments as its portrayal of college life in the mid-'60s evolves. The efforts of Ralph (a delightfully funny Jesse Hinson), as an encylopedia salesman from another college who is trying too hard to ingratiate himself into the household is unforgettable. So too is the visit of the landlord Mr. Willis (Kale Browne). Andrew Joffe (Bream) and Jesse Hinson (double cast as Effing) are the two bumbling cops following up on a complaint.

Then there is the hysterically funny arrival of Shelly (Samantha Richert) as the flower child who is only comfortable when sitting under a table. At those moments, "Moonchildren" is one of the most satirical and witty plays ever written. There are others who are less amusing, like Carter Gill as Norman, the serious math grad student who is the butt of many jokes and goes off the deep end of protesting the war. Kathy (the aforementioned Kuhling) is torn over which guy, Aaron Costa Ganis (as Dick) or Hale Appleman (as Bob), to sleep with. At the same time, Ruth (Miriam Silverman) plays the game just for the hell of it. Finally, there is the appearance of Uncle Murray (David Wade Smith) bringing bad news.

This is Karen Allen's second time directing the offbeat play. |

Staged in the smaller Unicorn Theatre at the Berkshire Theatre Festival, the play is no more mainstream today than during its first American outing at Washington, D.C.'s Arena Stage. It was a modest hit, so David Merrick moved it to Broadway, where it proved to be a disaster, closing after 16 performances.

Part of the "why" that happened might be because it posed the question "What values do you commit to after you have rejected the traditional ones?" without ever giving an answer. Even in 1974, when the country was still divided, "Moonchildren" was ahead of its time. Most Broadway ticket buyers in those days were part of what came to be known as the "silent majority" of center-right believers in the established order. The counterculture is what made off-Broadway grow, and then off-off Broadway. For all its humor, "Moonchildren" had an equal portion of angst and so it did not make for an escapist evening of theater. Its ideas were unfinished as well, which seemingly reflects the confusion of the times.

The play did find its audience off Broadway at the Theatre de Lys, where it ran for a year in 1973-4. I first saw it at the Charles Playhouse in Boston in 1974, where it played seemingly forever. It did well in college towns since it is the first play I can recall that showed cohabitation, marijuana and the growing opposition to the war in Vietnam.

In the end, "Moonchildren" is both delightful and infuriating. The lighter moments bring moments of delightful nostalgia but the serious ones are far too unfinished. As we used to say: "Wow, that's heavy, man ... heavy."

Larry Murray is a contributor to iBerkshires.com and offers reviews and arts news from around the region at Berkshire On Stage.