Movie Reviews

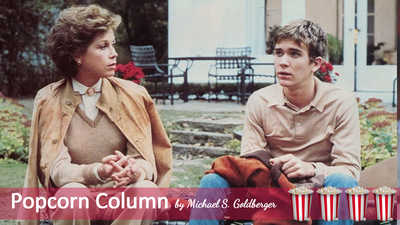

'Ordinary People': The Truth Will Set You Free

In thinking back on those salad days through rose-colored glasses, Dave's pretty Mom looks just like Mary Tyler Moore's Beth Jarrett, the female lead in Robert Redford's "Ordinary People," a beautifully embroidered opus about the tragic chink in the armor of a family of privilege. She likes things just so. Well, gosh, who doesn't?

'Planes, Trains and Automobiles': Conveys Friendship

What Hughes so passionately delves amidst the slapstick, cacophony and nutty incongruity of two vastly diverse men tossed into screwball circumstances is that, while you rarely make new friends in adulthood, if you do it is a blessing.

'My Man Godfrey': High-Class Struggle

What's actually funny is that conversations like the following might very well be taking place inside the mansions you survey on a Sunday drive. Y'know, those exurban castles that make you dizzyingly ponder, who lives there?

'My Favorite Year': Vintage Laughs

The pairing makes for a heartwarming, soulful commentary about the human condition, wonderfully evoked in a series of deliciously memorable moments, stitched together with notable comic savvy.

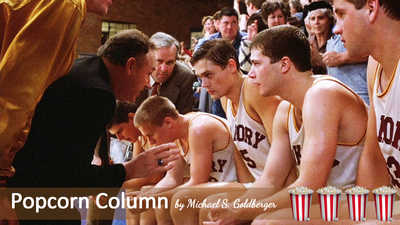

'Hoosiers': A Tale of Two High Schools

To the backdrop of provincial America, circa 1951, playing counterpoint to Myra and Norman's pithy, running contemplation of the human condition, Shooter's tragicomic interjections win the camera's favor with the near imperceptible finesse of a shooting guard stealing the ball.

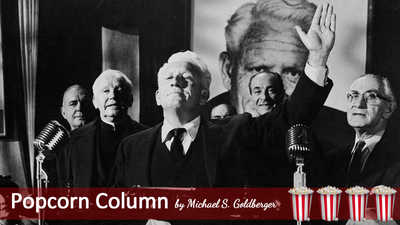

'Mr. Smith Goes to Washington': When the Good Guys Win

We anguish, laugh, smile and are put on tenterhooks as Mr. Smith, going through every mental and physical contortion, pleads before the Congress his case for truth, justice and the American way with a fervor perhaps only equaled by Daniel Webster's petition before the Devil.

'Peggy Sue Got Married': Life, on Second Thought

While the usual moral lessons about the 20-20-hindsight, a la "It's a Wonderful Life" (1946), integral to tales of time travel counsel us not to beat the horse that brought us to our present circumstances, there is a refreshingly delivered, stardust quality in Peggy Sue's genre update.

'Fatso': The Diet of Pagliacci

Alas, mixed into each laugh-evoking whimsy about the rituals and idiosyncrasies that play into pigging out, there lies in wait the dark truth. And while you're feeling terrible about what society erroneously labels a lack of willpower, thoughts about the impoverished, starving millions not blessed with your curse of overabundance doesn't help.

'The Last Hurrah': Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Politics, But Were Told Not to Ask

It's cheap, divisive, and keeps two levels of the underclass in tow. Inequitably overtax the bourgeoisie and there you've funded your dominion. It's old school. When you're the minority that's been in power since time immemorial, you get rather canny at controlling the majority.

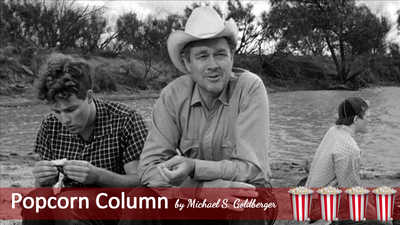

'The Last Picture Show': End Credits in a Texas Town

Yet, for all the adult themes set against this backdrop of fatalism and resignation, sure as a tree grows in Brooklyn, a coming of age tale in rural Texas won't be denied its albeit brief day in the sun.

'Friendly Persuasion': Love, Quaker Style

Now, Jess Birdwell, a handsome, strapping fellow who could probably lick many times his weight in such misguided naysayers, feels no need to prove his fearlessness. Real heroes never do.

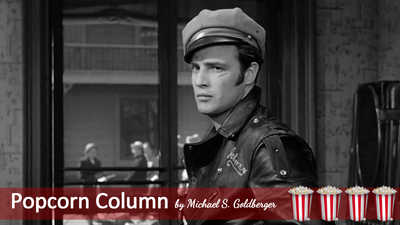

'The Wild One': Wandering Rebel

Everything else about the film inspired by the so-called Hollister Riot of 1947, wherein all hell broke loose when 2,000 members of the American Motorcyclists Association descended on that California town, Fourth of July Weekend, is up for conjecture.

'Dave': Would Totally Wear a Mask

The beauty of the parable at the heart of director Ivan Reitman's "Dave" (1993) is that the title character isn't beholden to the moneyed scourge that features itself the ruling class. He is the sorcerer's apprentice but with a conscience and a moral purpose, free to right the wrongs that have preceded his ascendancy.

'Being There': On the Square

What we sense in Chauncey is an aura and impetus totally bereft of such crass dynamics. But whether he is just as advertised or the genius prophet essentially adopted and taken in by Melvyn Douglas' industrial giant, Ben Rand, trusted advisor to Jack Warden's president, his naivete, or what passes for it, invokes a refreshing purity.